In Norse mythology, the sun and moon are symbolized as siblings who drive celestial bodies while being pursued by wolves; on occasion, they are depicted merely as inanimate objects. It is striking that written sources like the Poetic Edda and the Prose Edda reference them infrequently, yet a comprehensive examination of these texts alongside findings from the pre-Viking era illustrates their significant role in ancient Scandinavia.

The Sun and Moon in Norse Texts

Contrasting with Roman tradition and aligning more closely with modern German, “Sol” (sól in Old Norse) is a feminine name whereas “Luna” (máni) is masculine. In “Völuspá,” a poem where a seer reveals insights about the world’s origins and fate, their kinship is elaborated upon:

“Sol, sister of Luna,

Shone from the south,

With her hand

Over the sky’s edge;

Sol did not yet know

Where her home would be,

Luna did not yet recognize

His masculine power.” (stanza 5)

In the “Ballad of Vafthrudnir,” where Odin contends with a giant in a mythological knowledge contest, they seem to be personified. The father of Sol and Luna is named Mundilfari, which likely translates to “the returner,” hinting at the cyclical movements of celestial bodies:

“Named Mundilfari,

Father of Luna,

Also of Sol;

They will float

Day after day in the sky,

Indicating the hours.” (stanza 23)

For the Norse people, the day began with night and the year with winter.

Luna is mentioned first, and “Mundil” may be connected to “mund,” indicating a period of time, reflecting that for the Norse, the day hailed from night and the year commended winter’s arrival. The “Ballad” narrates how Fenrir, one of Loki’s monstrous children, would swallow the sun. Fenrir was known for biting off Tyr’s hand while being restrained with a magical rope. The scene depicting the sun being devoured by a monster could symbolize the sun’s rising and setting, or perhaps eclipses observed by ancient peoples, evoking fear in the face of such occurrences.

“As soon as Fenrir devours

The elfish wheel (the sun),

She gives birth to a daughter;

When the gods perish,

The creature follows her mother’s paths.” (stanzas 46-47)

These events are reiterated in “Völuspá,” where a seer foretells that one of Fenrir’s children, born from a giantess, would steal the moon. In other segments of “Völuspá,” which describe the signs of the gods’ demise and the impending battle known as Ragnarök, the sun turns black while the earth submerges in the sea; thus, it is not portrayed as a personified entity.

Using these fragments, Snorri Sturluson, an Icelandic scholar from the 12th century, attempted to weave a coherent narrative, including details found nowhere else. In “Gylfaginning,” the first section of his Prose Edda, he recounts a legendary Swedish king named Gylfi who embarks on a journey to broaden his wisdom. Amid countless events, the king questions the deities about the origins of the sun and the moon. According to Snorri, a man named Mundilfari has two beautiful children, and he weds his daughter Sól to a man named Glen. This reckless action angers the gods, who “take the siblings and place them in the heavens, and Sól drives the horses pulling the chariot of the sun crafted by the gods to illuminate the world with radiant light from Muspellheim” (Faulkes, 2005). Muspell was the realm of fire and home to fire giants.

Solar Imagery in Mythology

The narratives available regarding the Norse sun myth are remarkably scarce, despite numerous archaeological discoveries highlighting its immense significance to Bronze Age societies. This could be attributed to loss or evolution of materials or the fading significance of these deities as their attributes merged with others. Evidence pointing in this direction includes the portrayal of the sun’s chariot. The sun’s daytime journey in a chariot, and its night voyage by boat beneath the sea, was a near-universal pattern among early European civilizations. Additionally, Norse myths contain depictions of fertility gods such as Freyja, Freyr, and Njord, which are vaguely associated with the sun. Furthermore, the sun’s movement through the sky is linked to seasonal changes and plant growth.

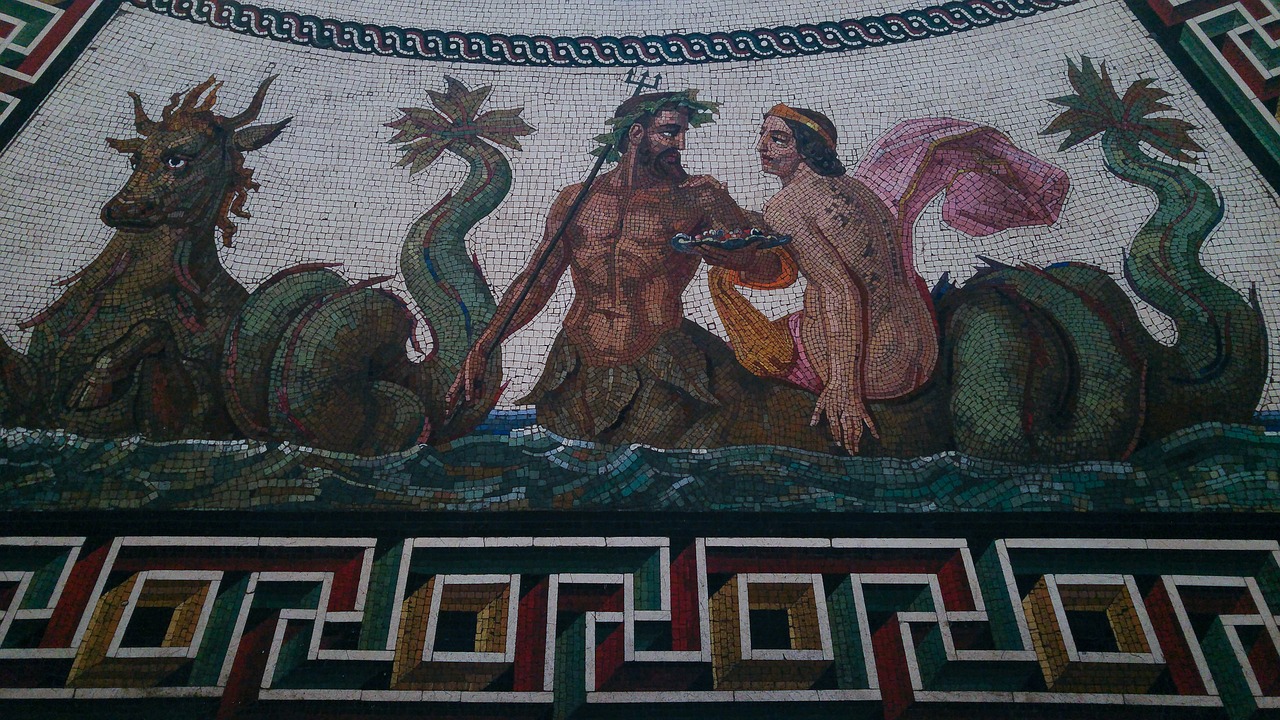

In prehistoric Scandinavia, images of a sun carried by men in ships or chariots can be found on stones within graves, sun-shaped shields, and belt plaques. The famous Trundholm sun chariot, dating from around 1400 BCE, shows the sun in its eternal journey, placed on a cart drawn by a horse, all resting on a structure supported by wheels suggesting perpetual motion. The Edda also recounts how the sun is pulled by two horses across the heavens, hinting at a synthesis of the solar myth with the image of a deity in a chariot. Similar traveling deities appear in the Iron Age Gundestrup cauldron, surrounded by ornate decorations and animals, showing intricate scenes, such as a procession of warriors and a horned god. Stone carvings from Gotland reveal images of rotating discs and riders, while finds from Kraghede, Vendsyssel, and Langå in Funen bear witness to the ritual chariots accompanying the powerful to their graves.

When discussing the Germanic tribe of the Suebi, the Roman author Tacitus, in his ethnographic work “Germania” from the 1st century CE, describes the sacred chariot of the earth goddess Nerthus located in a forest on an island where rituals took place. He narrates that the consecrated chariot was draped in fabric, could only be touched by a priest, and weapons were prohibited during its interaction with the human community. Days were filled with merriment until the goddess was washed in a concealed lake. Nerthus, the goddess’s name, correlates with Njord in Old Norse, a male deity and patriarch of the Vanir family of gods. This raises questions about whether they were initially separate deities that eventually merged into one, sharing traits with their offspring Freyr and Freyja. The presence of male priests in the worship of Nerthus and female priestesses for Freyr suggests the existence of counterparts. Nevertheless, Norse mythology assigns a different wife to Njord named Skadi, associated with skiing and winter.

The deities in chariots, associated with vegetation and growth, may have incorporated the roles of solar gods.

In “Ynglinga Saga,” Snorri recounts a legendary epic beginning his chronicle of Norwegian kings, humanizing the gods, with Freyr ruling as the king of Sweden after Njord. During his reign, days were filled with peace, and seasons shifted favorably. After his death, he was worshipped as a god of the harvest. These deities, traveling in carts that brought vegetation and growth, could be recognized as sun gods.

Alongside the evident connection between land fertility and its annual revival, the sun’s fall toward a ship may signify death and the underworld. It is likely that the engravings featuring chariots and birds placed in graves were intended to guide or protect the dead. Furthermore, in Viking burial practices, horses held special significance as conduits between realms; thus, the image of the sun being drawn by horses could embody more than mere solar movement. Figures of birds or women with bird-like features might evoke hazy memories of Valkyries who led fallen warriors to Valhalla, while others went to Fólkvangr, Freyja’s domain. Additionally, Odin, the god characterized by leadership and the capacity to instigate wars, could transform into an eagle, a symbol of power. Hence, these elements—the chariot, wheel, bird, and horse—intertwine with the notion of an underworld, subtly suggested by the solar chariot’s motion.

The other vibrant image popular in the Bronze Age, that of the sun in a boat, can easily parallel traditions elsewhere, such as the Egyptian sun god Ra or the Greek Apollo, who offered protection to sailors. This imagery is applied to shields; in Snorri’s poetic teachings, a shield may be referred to as a “skipsól,” literally a ship-sun, or “hlýrtungl,” a bow-luna.

Were They Solar Deities?

Determining whether Freyr and Freyja can be deemed solar deities presents a complex challenge. Freyja’s connection to the sun can only be inferred indirectly from her qualities, including her resplendent appearance and treasures like Brisingamen, a necklace that glows like fire. It has been suggested that she serves as a template for Valkyries, warrior maidens adorned with shields. If one accepts the association of shields with the sun and acknowledges Freyja’s chariot journeys and her glowing treasures, along with her tears of red gold, then a solar connection could emerge.

Freyr’s solar dimension can be gleaned from various mythological details. In “Gylfaginning,” he is described as the foremost of the gods, and his sister is called the most glorious of goddesses: “He who governs rain and the sun, consequently, the fruits of the earth, enjoys prosperity and peace in asking” (chapter 24). Besides fertility elements suggested in this quote, factors linked to the solar realm also emerge: his boar, Gullinbursti, with golden bristles, his gleaming servant Skirnir, and his ship that transforms into a sun image. At the world’s end, Freyr will fight the fire giant Surt, which could reference the sun’s destructive aspect. Regardless, considering Freyr’s qualities of providing prosperity and good harvests, he may imply a solar role.

However, it is essential to remember that Norse gods frequently had multifaceted roles, and given the inconclusive data, labeling Freyr and Freyja as true sun deities would be an overstatement. Historically, the pagan solar or lunar deities revered by Scandinavians before the Viking Age largely fell into oblivion around the time the Norse myths were penned. Speculation on whether their traits amalgamated with other deities exists but remains uncertain. Interestingly, one of the Merseburger spells, two charms written in Old High German from a 9th-century manuscript, mentions a figure named Sunna in the context of invoking deities to heal a horse’s leg—potentially a faint trace referencing the original sun goddess.