The Orpheus Myth: Its Enduring Influence in Opera

The Myth

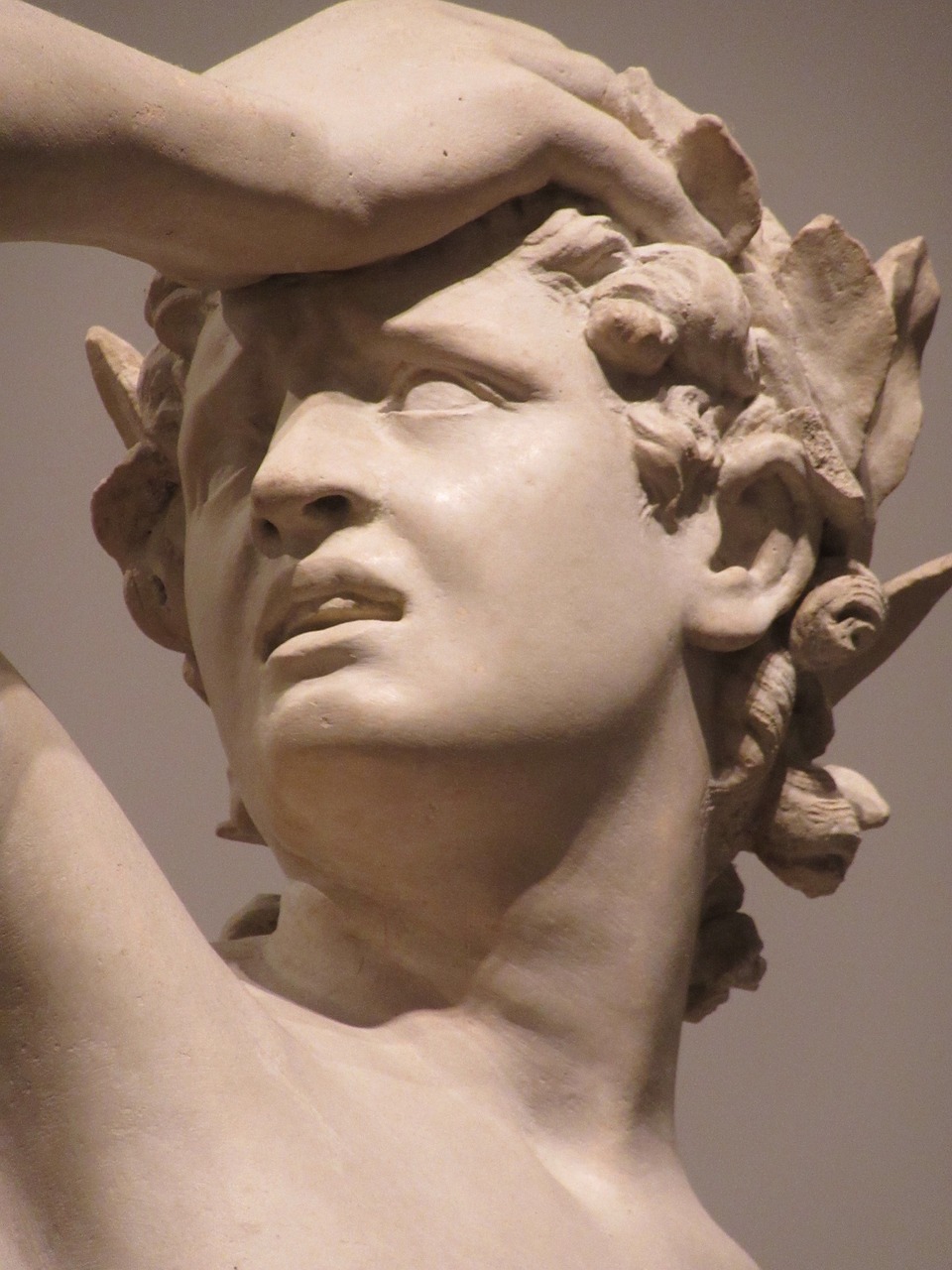

The narrative of Orpheus originates from Ancient Greece, evolving from even more ancient tales. The most celebrated retellings are crafted by renowned Roman poets, Virgil and Ovid. Orpheus is depicted as an extraordinary poet and musician whose enchanting melodies from the kithara—a stringed instrument akin to the lyre—captivate all of nature; animals, stones, and trees resonate with the cadence of his music. Tragically, shortly after his marriage to the nymph Eurydice, fate intervenes, leading to her untimely demise due to a viper’s bite.

Overwhelmed with sorrow, Orpheus embarks on a perilous quest to the Underworld, determined to rescue his beloved. His musical prowess charms Cerberus, the formidable three-headed guardian of the entrance, allowing him passage to meet Hades and Persephone. Moved by his artistry, Hades grants Orpheus permission to reclaim Eurydice—with a critical stipulation: he must not gaze back at her during their ascent. Filled with hope, he sets off but, unable to hear Eurydice’s footsteps, doubt takes root in his heart. Near the exit, unable to resist, he turns to look at her, sealing her fate in eternal separation. Consumed by grief, Orpheus plays sorrowful melodies on his lyre until a group of Maenads descends upon him, ending his life. Even in death, his head continues to sing as it floats down the waters.

Orpheus and Opera

The Orpheus myth retains its significance due to its profound implications about the transformative nature of art, bridging existence and the afterlife, if only briefly. Throughout history, his figure has inspired numerous artists, poets, and composers. As poet Rainer Maria Rilke noted in the 1920s: “Once and forever it’s Orpheus, whenever there’s song.” The story exemplifies the profound influence music holds, which is noted by Laurence Cummings, the music director/conductor for “Orpheus: Monteverdi Reimagined.” The myth celebrates music’s ability to quell chaos and soothe even the savage heart, cementing its place in the earliest operatic works produced in 17th-century Italy.

The Orpheus myth was central to the inaugural operas, with Jacopo Peri’s “Euridice” emerging in 1600, followed by a contemporaneous version from Giulio Caccini, and Monteverdi’s “L’Orfeo,” which debuted in 1607 and derived its essence from Peri.

Orpheus: Monteverdi Reimagined

Composed specifically for a court performance during Mantua’s Carnival, Monteverdi’s “L’Orfeo” skillfully weaves together innovative musical techniques and dramatic narrative, establishing the foundation of what opera represents today. Interestingly, while typically tragedies end bleakly, Monteverdi concludes this tale with the divine intervention of Apollo, who elevates Orfeo to the heavens, where he recognizes Eurydice’s presence among the stars.

The production reinterprets the tale through a fusion of Indian and Western baroque musical traditions, bringing a fresh perspective to the age-old narrative. Keranjeet Kaur Virdee of South Asian Arts-uk emphasizes that merging cultures highlights music’s universal nature, as emotions of love and loss resonate across genres.

Connecting this myth to the narratives within Indian folklore, Kaur Virdee outlines parallels with tales like “Heer Ranjha,” which echoes the themes of love shared between a maiden and a gifted musician. Similarly, “Sorath Rai Diyach” features a shepherd musician entangled in a tragic fate, illustrating the intertwining of music and spirituality that both traditions share.

As musician Jasdeep Singh Degun notes, Indian classical music has perpetually retained its ties with the divine, establishing a ritualistic relationship between teacher and student, and integrating spirituality into every aspect of performance.

Orfeo ed Euridice

Following Monteverdi’s era, opera seria gained prominence, showcasing elaborate themes centered on virtuosity. Yet Christoph Willibald Gluck sought a departure from this excess. His composition “Orfeo ed Euridice,” premiered in Vienna in 1762, strived for simplicity versus the ornate styles of the time. Following a similar premise, the opera commences with the lamentation of nymphs and shepherds after Euridice’s death. Orfeo encounters Amore, who gives him an opportunity to retrieve Euridice with the caveat of not looking back.

Throughout the journey, the Furies serve as obstacles, but Orfeo’s music evokes compassion softening their harshness. Ultimately, a bittersweet reunion occurs, where miscommunication leads to Euridice’s second demise. Orfeo’s aria “Che farò senza Euridice” captures his anguish, marking a defining point of heartbreak, ending on a note of hope as Amore restores her life.

Orpheus in Contemporary Performances

Anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss viewed myths as dynamic entities capable of reflection and reinterpretation across cultures. Gluck’s “Orfeo ed Euridice” has significantly influenced numerous operatic and musical narratives, evident in Mozart’s enchantments and contemporary reinterpretations, such as rapper Testament’s modern retelling during the isolation of 2020.

In this adaptation, Testament metaphorically navigates an emotional underworld, echoing Gluck’s themes as he composes a narrative that intertwines lessons learned through a web of experiences. By employing musical cues reminiscent of the original opera, he crafts a hopeful remix of Orpheus’s poignant questions.

Through exploring these myriad interpretations of the Orpheus myth, we witness its profound influence on the arts, showcasing its unparalleled ability to resonate through time, captivating audiences across diverse cultures.