Among the multitude of deities revered in Roman mythology, Jupiter stands as the paramount god, revered as the offspring of Saturn and symbolizing thunder, lightning, and storms. The earliest inhabitants of what would transform into Rome believed they were safeguarded by ancestral spirits, prompting the addition of a triad of gods: Mars, the war deity; Quirinus, the deified Romulus overseeing the Romans; and Jupiter himself. Recognized as Jupiter Elicius, or the one who brings forth, Jupiter’s status as the greatest god solidified by the time of the Republic, with some of the old triad replaced by Juno (his sister and spouse) and Minerva (his daughter). His primary title, Jupiter Optimus Maximus, translates to “the Best and Greatest,” reflecting his position as the ruler of the gods.

Jupiter evolved from being a personal deity of the Etruscan kings to a central figure in the Republic, embodying light, triumph in battles, and protection in times of defeat. He was revered as Jupiter Imperator, the highest commander; Jupiter Invictus, the undefeated; and Jupiter Triumphator. In war, he was a guardian of Rome, while during peacetime, he ensured the welfare of its citizens. Typically depicted with a long white beard, Jupiter’s emblem was the eagle perched upon a scepter, which he held as he sat upon his grand throne. Much like Zeus, his reputation for ferocity often instilled fear, as he wielded the power to unleash his thunderbolts, though he typically offered warnings prior to delivering severe punishment, which was usually executed with the approval of other deities.

Jupiter in Roman Religion

Religion was an innate part of human societies through the ages, serving as a framework that explained various aspects of life, such as natural cycles and celestial movements. Deities defended people against foes, controlled nature’s forces, and rallied alongside them in combat. Gods permeated every aspect of folklore, with temples raised in their honor and sacrifices made to seek their favor. Prior to the dominance of monotheistic beliefs, including Judeo-Christianity, many cultures, including the Romans, practiced polytheism. They venerated numerous gods responsible for different domains, including war, agriculture, and fertility.

For the primitive Romans, faith and ritual were sources of solace and security, particularly during the nascent years of the Republic. Religion influenced nearly every facet of existence; critical decisions frequently involved divine consultation. Unlike the individualistic nature found in Christianity, Roman faith was communal and lacked sacred texts or doctrines. Instead, it revolved around the pax deorum, or the peace of the gods. The Romans engaged in rituals and supplications to win the gods’ grace and avert their wrath. While they generally embraced the belief systems of conquered peoples, they maintained a vigilant stance towards their official religion, regarding anything that threatened their societal structure with suspicion. This vigilance contributed to the persecution of Jewish and Christian communities during the reign of Nero and subsequent rulers. Thus, Jupiter and the pantheon of Olympians navigated through various societal changes from the Etruscans, across Republican and Imperial periods, and into the early rise of Christianity.

Temple in Rome

Around 509 BCE, a grand temple was constructed on Capitoline Hill, shared by Juno and Minerva, serving as a congregation site for sacrifices. This temple, the finest in Rome, boasted a substantial statue of Jupiter and housed the Sibylline Books—Rome’s oracles consulted in emergencies. Jupiter was honored with various prestigious titles: Invictus, Imperator, and Triumphator, denoting his significance in both civil and military facets of Roman life. Upon returning from military successes, generals would partake in a display known as a triumph, parading through Rome to Jupiter’s temple draped in purple robes, wielding a scepter, and riding in a chariot drawn by four white horses, surrounded by citizens, soldiers, and captive foes in chains. Once at the temple, the victor would offer a sacrifice and dedicate a share of the spoils to Jupiter.

To military leaders, Jupiter represented the valiant spirit of Roman forces. While celebrated in military contexts and regarded as a deity of warfare, he also functioned as a political force. The Senate required Jupiter’s endorsement before declaring war, and he served as the guardian of oaths and treaties, punishing those who broke their vows. No significant political maneuver was initiated without his sanction. Significant festivals such as the Ludi Romani, celebrated in September, were dedicated to him.

The Decline of Jupiter

Despite his revered status, Jupiter faced challenges and criticism. After Julius Caesar’s assassination, who had once served as Jupiter’s high priest, Augustus’ adherents established a cult of imperial worship. While Augustus himself denied divinity, successive emperors often embraced this status, with figures like Caligula declaring themselves divine and Galba claiming descent from Jupiter. Emperor Elagabalus controversially attempted to supplant Jupiter with Elagabal, a deity from Syria, transporting a sacred stone idol to Rome, leading to the construction of the Elagabalium on the Palatine Hill. Fortunately, Alexander Severus reinstated Jupiter in his rightful position, returning the stone to Syria and reinforcing the deity’s standing. In the third century, however, the cult of Sol Invictus emerged, presenting its own challenge, which was a god connected to soldiers. Yet again, Jupiter’s supremacy was reaffirmed by Diocletian.

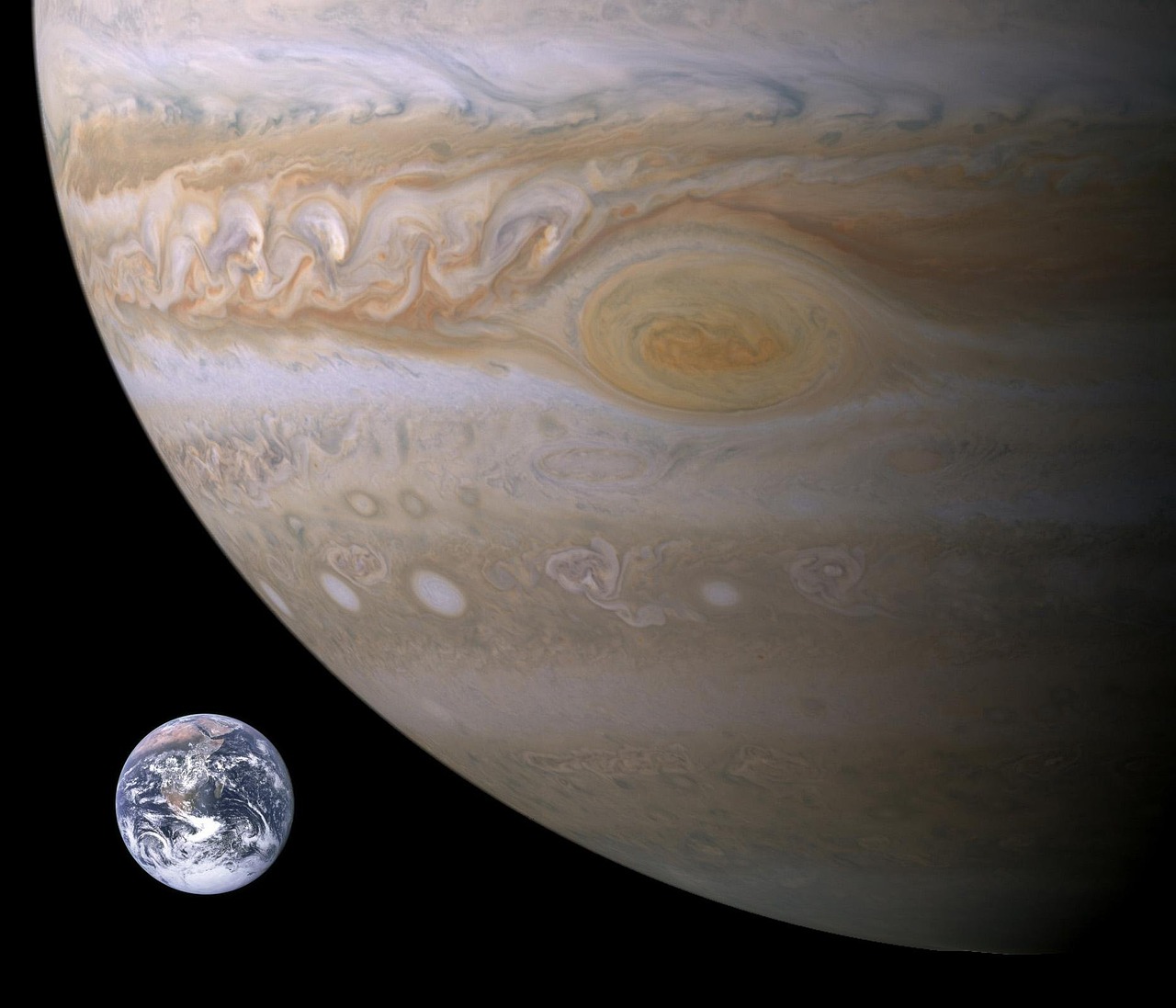

Ultimately, the rise of Christianity and the corrosive decline of the Roman Empire in the 5th century CE relegated Jupiter and other deities to mere mythological status. Their names live on through the solar system, identifying the planets: Jupiter, Neptune, Mars, Mercury, and Venus. Sadly, Jupiter’s legacy has been somewhat overshadowed by the reputation of Zeus, his Greek analogue. Nonetheless, throughout most of Roman history, he played an integral role in cultural and daily life, serving as a protector during times of conflict and tranquility alike. No matter the fate of emperors, Jupiter’s presence remained a constant in Roman society.