Saturn: The Agricultural God of Rome

Saturn, known in Roman mythology as Saturnus, shares a narrative similar to that of Cronus from Greek lore. Often portrayed in artwork brandishing a scythe, he is primarily recognized as a deity of agriculture, particularly associated with seed-corn. One of the key highlights in the Roman calendar was the Saturnalia festival, a vibrant celebration dedicated to him, alongside his prominent temple situated in the Roman Forum.

Greek Connections

The realms of Greek and Roman mythology are deeply intertwined, often appearing indistinct at a glance. Even though the deific names differ—Zeus became Jupiter, and Hades was transformed into Pluto—their societal functions and narratives largely remain constant. The Romans, upon their initial encounters with Greek culture, underwent a significant transformation, albeit somewhat reluctantly, adopting many Hellenic elements. The admiration for Greek culture was profound, leading affluent Roman families to enlist Greek educators for their sons. Literature, art, philosophy, religion, and various other aspects of life in Rome evolved significantly due to these influences. A prime example of this cultural amalgamation is Saturn, who found refuge in Rome after being cast out from Greece.

There is a debate among scholars regarding Saturn’s origins within Roman mythology, with some potential ties to the Etruscan deity Satre. However, such claims remain largely speculative. As Greek religious practices permeated Roman tradition, Saturn—often depicted with a scythe—became increasingly merged with Cronus, the Greek deity depicted as the universe’s sovereign who swallowed his offspring. Cronus is the progeny of Uranus (the sky) and Gaea (the earth). Following the Titanomachy, where Zeus and his brothers triumphed over the Titans, Cronus was banished from Mt. Olympus.

Legend of Saturn in Latium

Roman mythology posits that Saturn established himself in Latium, the prospective site of Rome, where he was welcomed by Janus, the two-faced deity symbolizing beginnings and endings. It was here that Saturn quickly took charge, even founding the city of Saturnia. During this golden age, he ruled Latium with wisdom, fostering an era of abundance and tranquility. This period closely linked him with agriculture, notably as a god of seed-corn, which explains his iconic representation in art with a scythe in hand. Saturn imparted agricultural knowledge to the inhabitants, promoting practices in farming and viticulture, while also guiding them away from “barbaric” practices toward a more civic and virtuous way of life.

The Saturnalia Festival

Although the specifics of Saturn’s mythology and role in Roman history are often debated by historians, two notable legacies endure: his temple and the Saturnalia festival. His temple, erected around 498 BCE at the base of the Capitoline Hill, functioned as a central repository for Rome’s treasury and official decrees. Following years of decay, it was revitalized during Emperor Augustus’s reign. The Saturnalia festival was one of the most eagerly awaited celebrations on the Roman calendar, occurring from December 17th to 23rd and signifying the winter grain sowing—although some historical accounts suggest it may have been celebrated in August. Despite Emperor Augustus’s attempt to shorten the festival to three days, subsequent emperors like Caligula and Claudius extended it back to five days, although citizens largely maintained the tradition for a full week. The festival, part of Numa’s calendar (Rome’s second king), directly preceded the festivity dedicated to Ops, Saturn’s consort and the goddess of harvest, who was also identified with the Greek goddess Rhea. Additionally, Saturn was associated with Lua, another ancient Italian deity.

The festival, similar to other Roman festivities, involved extensive feasting, drinking, and games. There were numerous banquets and activities, although accounts of gladiatorial contests and human sacrifices are disputed among scholars. A mock king presided over the festival, referred to as the King of Misrule or Saturnalicius princeps, while attendees exchanged gifts, usually simple items like candles or pottery figurines. A unique aspect of the celebration was the temporary freedom granted to slaves during the festivities. They were not required to don the traditional felt hat or pilleus and could wear leisure clothing. Moreover, roles were reversed as slaves commanded their masters, while the latter tended to the former.

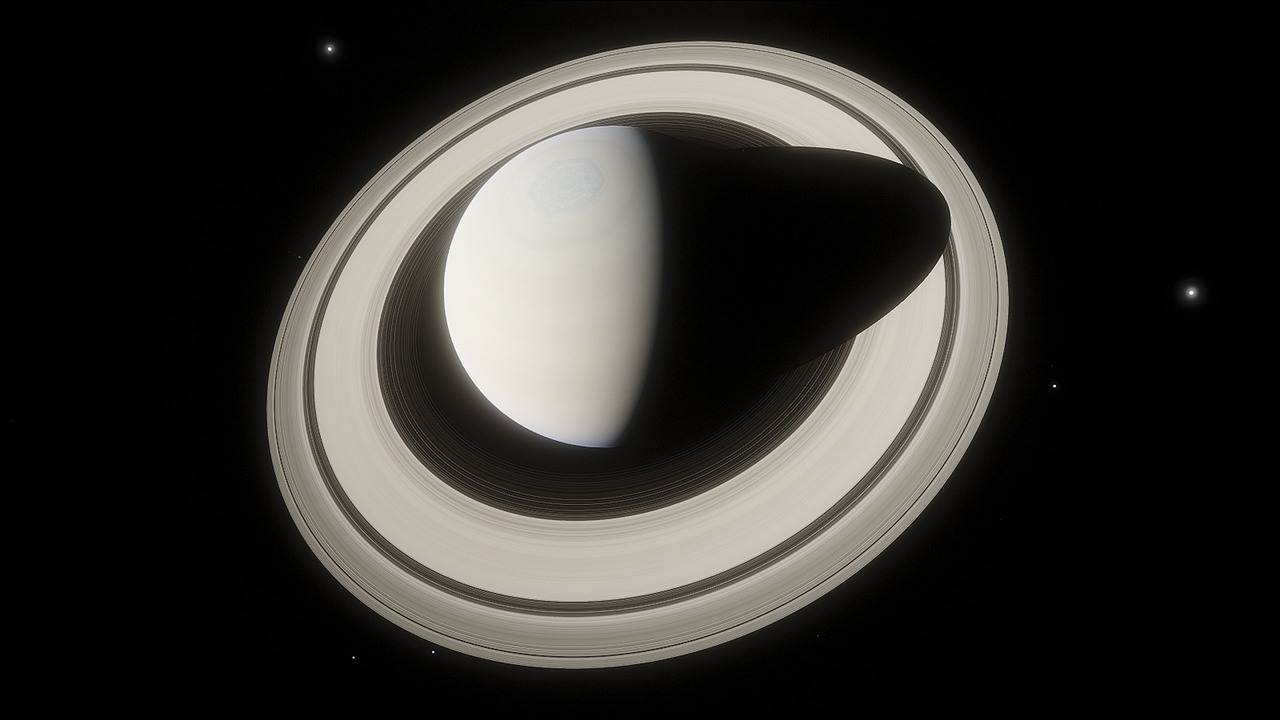

Though the vibrant Saturnalia and similar ancient festivals have considerably faded from contemporary practice, the legacy of Saturn remains in the cultural fabric of today. His name persists in our weekly calendar marking the end of the working week—Saturday. Additionally, we can gaze upon the planet Saturn in the night sky, a reminder of this long-remembered deity.