Understanding Ancient Egyptian Religion

Ancient Egyptian religion encompasses the rich tapestry of indigenous beliefs that evolved from the pre-dynastic era (4th millennium BCE) until the decline of traditional practices in the early centuries CE. This religion is inextricably woven into the fabric of Egyptian society throughout its historical development, which can be traced back to around 3000 BCE. Despite the potential for some ancient customs to persist, the transformation that led to the establishment of the Egyptian state provided a fresh context for religious beliefs.

Religious activities were deeply embedded in all aspects of life, challenging the notion of a unified religious system. Instead, it is more fitting to view religion against the backdrop of a range of non-religious human actions and societal values. Over the course of more than three millennia, the focus and forms of religious expression in Egypt underwent various changes. Nevertheless, consistency in character and style remained evident throughout its different periods.

It is essential to broaden the definition of religion to go beyond the mere worship of deities and human devotion. Religious practices included interactions with the deceased, divination, oracle consultations, and the application of magic, with these activities typically harnessing divine connections. Public religion in Egypt centered around two primary figures: the Pharaoh and the pantheon of gods. This duality underscores some of the most defining aspects of Egyptian civilization.

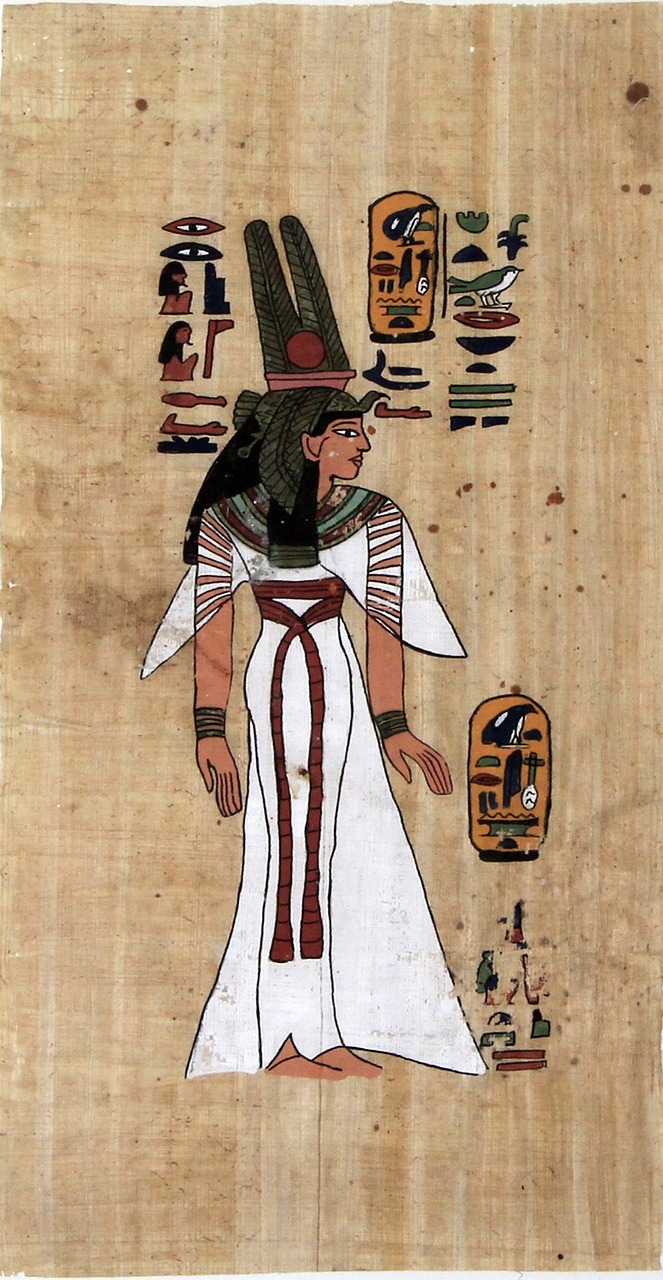

The Pharaoh possessed a unique position, serving as a bridge between humanity and the divine. He participated actively in divine realms, which included the construction of magnificent funerary monuments driven by religious motivations, intended for his afterlife. The diversity among Egyptian deities added to the complexity of their beliefs, characterized by distinct forms, some represented as animals or hybrids with animal heads atop human bodies. Among the most revered gods were the sun god—a figure who had multiple names, embodying various aspects and forming associations with other supernatural entities within a solar cycle—and Osiris, the god presiding over the dead and the underworld. Along with his partner, Isis, Osiris gained prominence in many aspects of worship during the first millennium BCE, a time when the focus on solar deities began to wane.

The Egyptians viewed their universe as a cohesive entity encompassing the deities and the current world, with Egypt being the focal point, surrounded by a chaotic realm. It was vital to uphold order, countering the potential for disorder that threatened their existence. The king’s role in society was to ensure that the gods remained benevolent, thereby sustaining order amidst disarray. This rather somber perception of the cosmos was largely linked to the solar god and the cyclical patterns of the sun. Such views served to legitimize the authority of the Pharaoh and the elite, underscoring their duty to maintain harmony.

Interestingly, despite the underlying pessimism, the grand narrative presented on monuments conveyed an optimistic outlook, depicting the Pharaoh and deities in a state of ongoing reciprocity and harmony, which, in turn, highlighted the fragility of this established order. The specific manifestations of this narrative were governed by decorum that dictated what could be depicted, how, and the contexts in which these depictions could occur. This adherence to decorum, coupled with affirmations of order, worked in tandem to reinforce their beliefs.

Much of what is known about these beliefs and religious practices originates from artifacts and texts produced for and by the Pharaohs and the elite. However, the spiritual life and practices of the lower classes remain largely undocumented. There is no compelling evidence to suggest a stark divide between the beliefs of the elite and those of the common people, though this possibility cannot be completely discounted.