The Legacy of Ra: Ancient Egypt’s Sun God

Ra, often referred to as Re, is an integral figure among the deities of ancient Egyptian religion, embodying the sun and vital life force. As one of the earliest gods in the Egyptian pantheon, Ra eventually merged identities with other strong deities such as Horus (Ra-Horakhty, the dawn sun), Amun (the midday sun), and Atum (the evening sun).

In Egyptian vernacular, Ra symbolizes the sun itself. This solar god represents not only the sun’s potent energy but personified the sun journeying in a celestial barge across the sky, culminating in a descent into the underworld. Every sunset signals his nightly battle against the chaotic serpent, Apophis, whose mission is to obstruct the dawn and undermine life on earth.

Scholar Richard H. Wilkinson emphasizes that Ra could be “arguably Egypt’s most important deity,” not just due to his connection with nourishment and daybreak, but because of how he influenced later gods. Amun’s rise as a preeminent god was significantly rooted in Ra’s mythology. Moreover, Horus, linked to the reigning pharaoh, follows a similar lineage as Ra, identified as the “father of kings.” Alongside Atum, he often appears in creation narratives, reflecting the intertwined nature of these divine identities.

Classification of Ra’s Roles

Wilkinson suggests a structured approach to understanding Ra’s multifaceted persona through five key aspects:

- Ra in the Heavens

- Ra on Earth

- Ra in the Netherworld

- Ra as Creator

- Ra as King and Father of the King

This framework is particularly pertinent when studying Ra, given his extensive powers, pivotal presence in Egyptian belief systems, and the longevity of his worship. Ra’s reverence emerged in the early days of the Old Kingdom (circa 2613-2181 BCE) and persisted for nearly two millennia until eclipsed by the advent of Christianity.

Early Manifestations and Worship

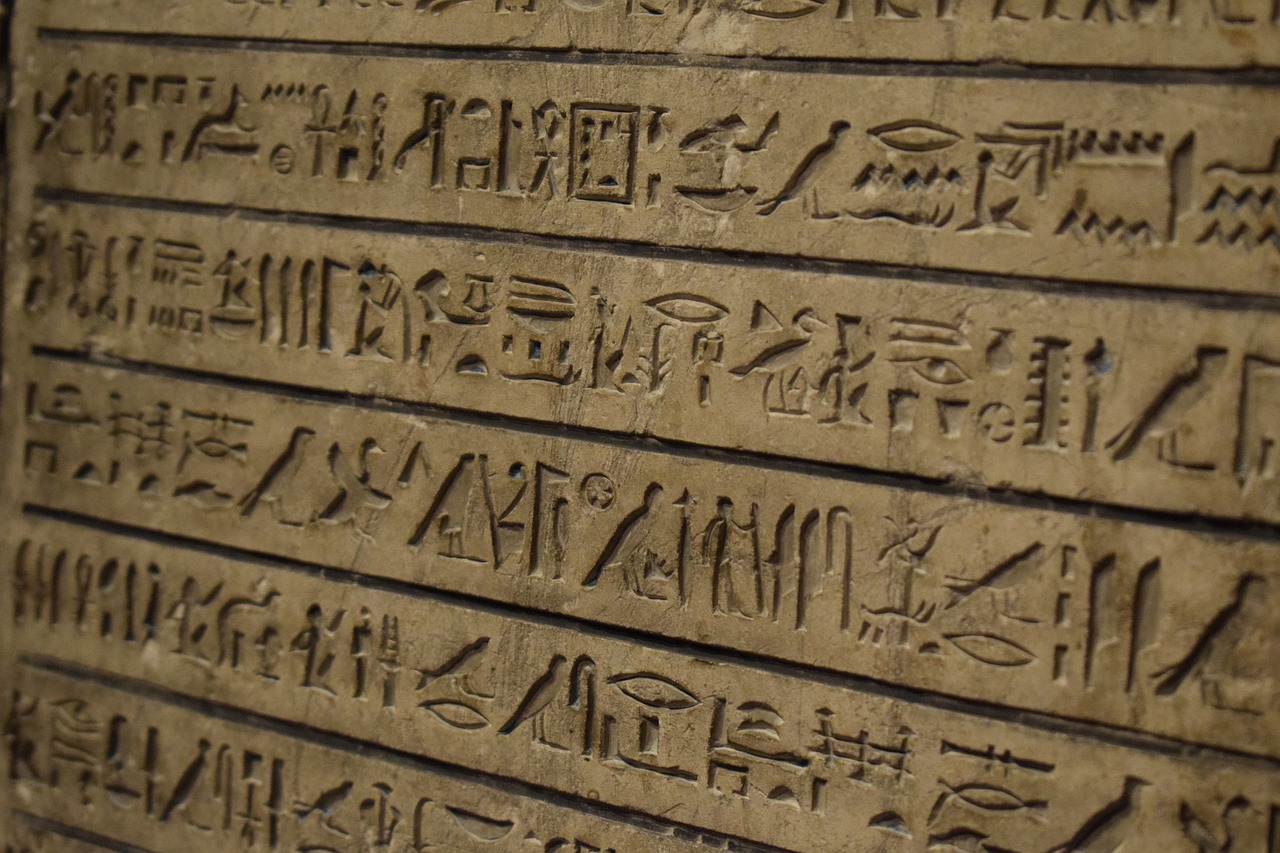

Ra’s earliest references can be found in the Pyramid Texts, dating back to around 2400-2300 BCE, which are considered the oldest religious texts globally. These inscriptions illustrate Ra as the soul-catcher of deceased kings, guiding them to the lush Field of Reeds. His worship was firmly established during this period, particularly centered in the city of Iunu—known historically as Heliopolis, “the city of the sun god.” Within these texts, Ra is not only depicted as a supreme deity but also as the essence of cosmic order.

Typically portrayed as a falcon-headed figure adorned with a solar disk, Ra is identified as the Self-Created One. In creation lore, he is portrayed as Atum standing upon the nilotic ben-ben, the primordial mound, bringing forth existence from chaos. Through the power of magic divine—Heka, a force intertwined with the deities—he accomplishes creation and transformation.

Ra’s worship can be traced back to the Second Dynasty and involved sacrificial rites in a range of temples. By the 5th Dynasty, kings began associating their rule with Ra, leading to the establishment of monumental temples, including those reflecting the living embodiment of Ra through the Mnevis bull.

Ra in the Heavens

The connection between Ra and the sky is highlighted in ancient texts, particularly the Book of the Heavenly Cow. This narrative illustrates Ra’s ascension from Earth to the heavens, driven by the anger at humanity’s rebelliousness and ingratitude. Fearing the potential coup, Ra convenes with the other deities for counsel, ultimately unleashing the Eye of Ra, personified here by the goddess Hathor, who is set free to ruin humanity.

The ensuing carnage spurs Ra’s regret, leading to his plea for her restraint. Transforming through her rage, Hathor becomes Sekhmet, oblivious to Ra’s entreaties. To soothe her, Ra concocts a plan involving beer dyed to mimic blood, allowing her to return to her former self, establishing a bond once again with humanity.

Exhausted from humanity’s strife, Ra requests the goddess Nut to bear him into the skies. Nut transforms into a cosmic cow, elevating Ra’s reign to the heavens where he organizes the divine order, leaving the governance of earth to the other gods.

Ra on Earth

Before his ascension, Ra directly governed his creation, with the natural world reflecting his essence. His influence was visible in the sunlight and resulting flora, driving the agricultural cycle. Notably, Ra directed the three annual seasons of the Egyptian calendar, significantly impacting the Nile’s inundation and the crop cycles.

Houses of Life were temples where the god of writing, Thoth, and his counterpart Seshat safeguarded the scribes’ writings. The preservation of knowledge, pivotal for societal order, was believed to be inspired by Ra himself, identifying the written word as a direct emanation from his divine spirit.

Ra in the Netherworld

Upon nightfall, Ra’s barque would transition into the Ship of a Million Souls, ferrying the justified deceased to their eternal paradise. At this phase, Ra melds with Osiris, the ultimate judge of the dead, revealing a dual identity—Ra-Osiris, overseeing the passage of souls and confirming the justified before navigating through the underworld’s shadows.

Throughout this nightly journey, Ra and his crew—assisted by the justified souls—battled Apophis’s attempts to extinguish their light. This struggle exemplified the perpetual conflict between order and chaos, with the dawn representing Ra’s victory and a new day for the living.

The New Kingdom’s Book of the Dead elaborates on the soul’s judgment, where Osiris weighs the heart against Ma’at’s feather of truth. Ra’s presence is intertwined within this process, even as Ma’at symbolizes order and fairness.

Ra as Creator

Creation myths attribute the establishment of the cosmos to several gods, notably Ra, Atum, Ptah, and Neith, albeit Ra’s essence pervades each manifestation. The prevailing narrative describes the universe as formless water until Ra emerged from the primordial mound, from which followed a sequence of creation involving divine offspring establishing the world’s features.

Ra’s act of creation led him to produce the initial deities, with authority and intellect birthed from his divine essence. Upon anticipating the need for humanity, Ra’s tears fell from joy, proliferating the fertile soils and giving rise to men and women.

Ra as King and Father of the King

In ancient Egyptian culture, balance was paramount, a quality embodied by the pharaoh who governed under Ra’s influence. The 5th Dynasty king, Userkaf, established Ra’s cult as a quasi-state religion, legitimizing his reign through the king’s divine mandate. This initiative catalyzed the construction of numerous temples throughout Egypt.

Userkaf’s successors perpetuated this tradition, affirming the alignment of kingship with Ra’s divine authority. He was revered as the “King and Father of the King,” reinforcing the connection between the gods and their earthly representatives.

With time, Horus and Osiris became linked to the ruling figure’s divinity during life and after death, respectively, though Ra’s underlying presence was acknowledged as fundamental to their authority.

Conclusion

Ra’s influence extended beyond mere solar illumination; he symbolized life, creativity, and cosmic order that permeated the Egyptian pantheon. Prominent goddesses like Bastet, Hathor, and Isis were conceptual connections of Ra, highlighting his vital force in all forms.

Akhenaten’s reign saw Ra worshiped predominantly, as his deity Aten mirrored Ra closely, yet once the older belief systems were reinstated under Tutankhamun, Ra regained prominence among Egyptian worship. Throughout Egyptian art, his motifs persisted, illustrating how deeply his essence enriched the spiritual framework until, with Christianity’s rise, the ancient veneration waned.