Amun, known through various names such as Amon or Amun-Ra, is a significant deity in ancient Egyptian mythology, recognized as the god of the sun and air. His veneration began in Thebes, emerging as a prominent divine figure around the onset of the New Kingdom (circa 1570-1069 BCE). Throughout this era, the Amun cult flourished and maintained its influence over centuries as one of Egypt’s most revered spiritual traditions.

Typically, Amun is represented as a bearded figure adorned with a dual-plumed headdress. In later depictions, particularly after the New Kingdom, he is portrayed either with the head of a ram or as a ram itself, linking him to fertility in his guise as Amun-Min. His name translates to “the hidden one” or “mysterious in form,” distinguishing him from other Egyptian gods by being a universal creator who embodies every facet of existence.

Origins and Rise of Amun

Amun first appears in the Pyramid Texts (circa 2400-2300 BCE) as a local god of Thebes alongside his partner, Amaunet. During this period, the war deity Montu was revered as Thebes’ supreme god, while Atum, linked to creation, was viewed as the creator deity. Montu served to safeguard the city, and Atum emerged from chaos to shape the world. Initially, Amun’s role was minor, associated mainly with fertility and regarded as part of the Ogdoad—an ensemble of eight gods symbolizing fundamental elements of creation.

Despite his lesser status compared to Montu and Atum, Amun encompassed the theme of “hiddenness,” uniquely allowing individuals to interpret his deity based on their needs and perspectives. This characteristic might facilitate Amun’s flexibility, allowing him to resonate as a universal representation of all aspects of life, from darkness to light.

Around 1800 BCE, the Hyksos, likely originating from the Levant, began their occupation of Lower Egypt, making Theban authority diminished by circa 1720 BCE. This period is recognized as the Second Intermediate Period, during which the Hyksos ruled. However, with the ascendance of prince Ahmose I around 1570 BCE, the Hyksos were expelled, and Amun’s rise to significance surged, marking him as a central figure in Thebes’ religious landscape.

Authority Among the Gods

By the New Kingdom, Amun emerged as the leading deity, claiming titles such as “The Self-Created One” and “King of the Gods.” He became associated with Ra, the sun god, historically related to Atum of Heliopolis. Despite this syncretism, the two remained as distinguished entities. In the fusion of attributes, Amun-Ra evolved as a deity who encompassed both the invisible spirit (symbolized by the unseen yet felt wind) and the visible, vital sun.

Amun’s worship grew such that in some scholarly views, ancient Egyptian religion approached a monotheistic narrative centered around him. His elevated status played a role in the unexpected religious shifts during the reign of Akhenaten, who controversially attempted to prioritize worship of Aten, stirring conflict with Amun’s established cult, primarily driven by the wealth of Amun’s priesthood.

The Worship and Symbolism of Amun

Once Amun asserted dominance among deities, he embraced numerous titles reflecting his multifaceted nature. The Egyptians recognized him as “Amun rich in names,” emphasizing that his true essence could only be appreciated through the myriad attributes interwoven in his divinity. Known as “The Concealed God,” Amun’s characteristics were tied to the air and the wind, palpable yet not visible. As he further merged with Ra, Amun adopted attributes of fertility, connecting him to the older deity Min. His identity expanded to encapsulate aspects of warfare as well.

In the grand temple of Karnak, Amun served as a divine pharaoh, connecting his essence not only with divine power but also with the common people’s struggles. His presence was believed to be ubiquitous, often answering the prayers of Egyptian kings in battle and aiding those in need.

During the New Kingdom, Amun’s popularity soared, resulting in extraordinary architectural accomplishments. His primary temple at Karnak remains the largest ever constructed for a deity, showcasing the extraordinary admiration for Amun across the land.

Amun and His Priesthood

King Ahmose I’s extensive resources enabled him to erect ceremonial structures befitting Amun, but ultimately, the wealth amassed by Amun’s priests became unparalleled. By Amenhotep III’s reign (1386-1353 BCE), the priesthood wielded vast influence, often rivaling the pharaoh himself. Although Amenhotep III attempted to diminish their power through the elevation of the sun disk deity Aten, the cult of Amun continued to prosper, remaining integral to the spiritual lives of the people.

The religious landscape underwent seismic shifts with Akhenaten’s rule. Following a brief retention of prior practices, Akhenaten forsook traditional deities, elevating Aten to a state of sole worship. His actions triggered a suppression of Amun’s worship and his priesthood. Even so, many Egyptians maintained their religious roots in secrecy.

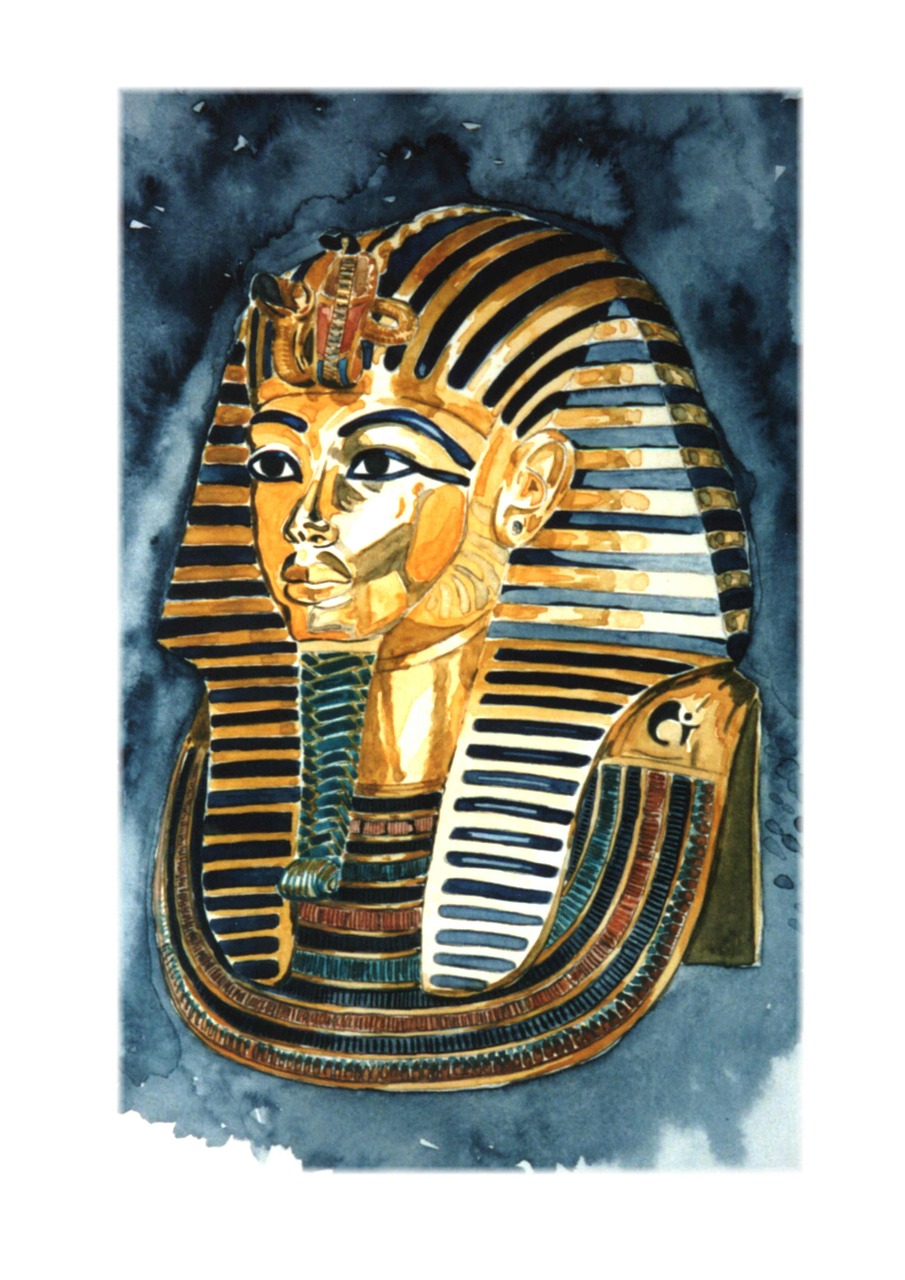

Upon Akhenaten’s death, his successor, Tutankhamun, reverted to traditional worship practices, reinstating the veneration of Amun while diminishing Aten’s influence. The priests regained their stature, and under Horemheb’s reign, attempts were made to expunge Akhenaten’s legacy by reinstating the old gods.

Amun’s Legacy

Amun’s worship sustained its popularity despite the rise of other deities like Isis. The position of “God’s Wife of Amun,” enhanced under Ahmose I, conferred both religious and political power, with Kushite kings adopting Amun into their own belief systems. As time advanced, despite various societal upheavals, including conquests and changing religious paradigms, Amun remained an emblematic figure, a protector of the common folk, and an influential god in both Egypt and Nubia.

Even as beliefs evolved with the advent of Christianity, Amun continued to be recognized as a powerful deity until fading into history, illustrating the resilience of his cult through numerous epochs.