A few years back, the British Museum hosted an exhibition entitled Living with Gods, which suggested that religion is essential to our human experience. Despite some reservations I had about the exhibition, this concept intrigues me — if religion is vital, what role does it play in our lives? One fundamental aspect of religion is its ability to contextualize our surroundings, crafting narratives that guide us through the complexities of existence. While this may hold less significance in our contemporary world dominated by scientific understandings, the ancient Egyptians viewed their deities as integral components of their worldview, with many of their gods representing natural forces personified for comprehension.

Among these deities is Shu, the god of air and sunlight, specifically embodying the element of dry air, with Tefnut, his sister, personifying moisture. This division makes sense given Egypt’s arid climate; such distinctions might seem odd in a different environment, such as Britain. Shu, being the embodiment of air, is represented as wind, indicating his omnipresence. Unlike the Greek pantheon, where gods wield control over specific forces, Egyptian deities manifest as those forces. The Coffin Texts record Shu proclaiming, “I am Shu… my clothing is the air… my skin is the pressure of the wind,” conveying the idea that to feel the breeze was to experience Shu himself.

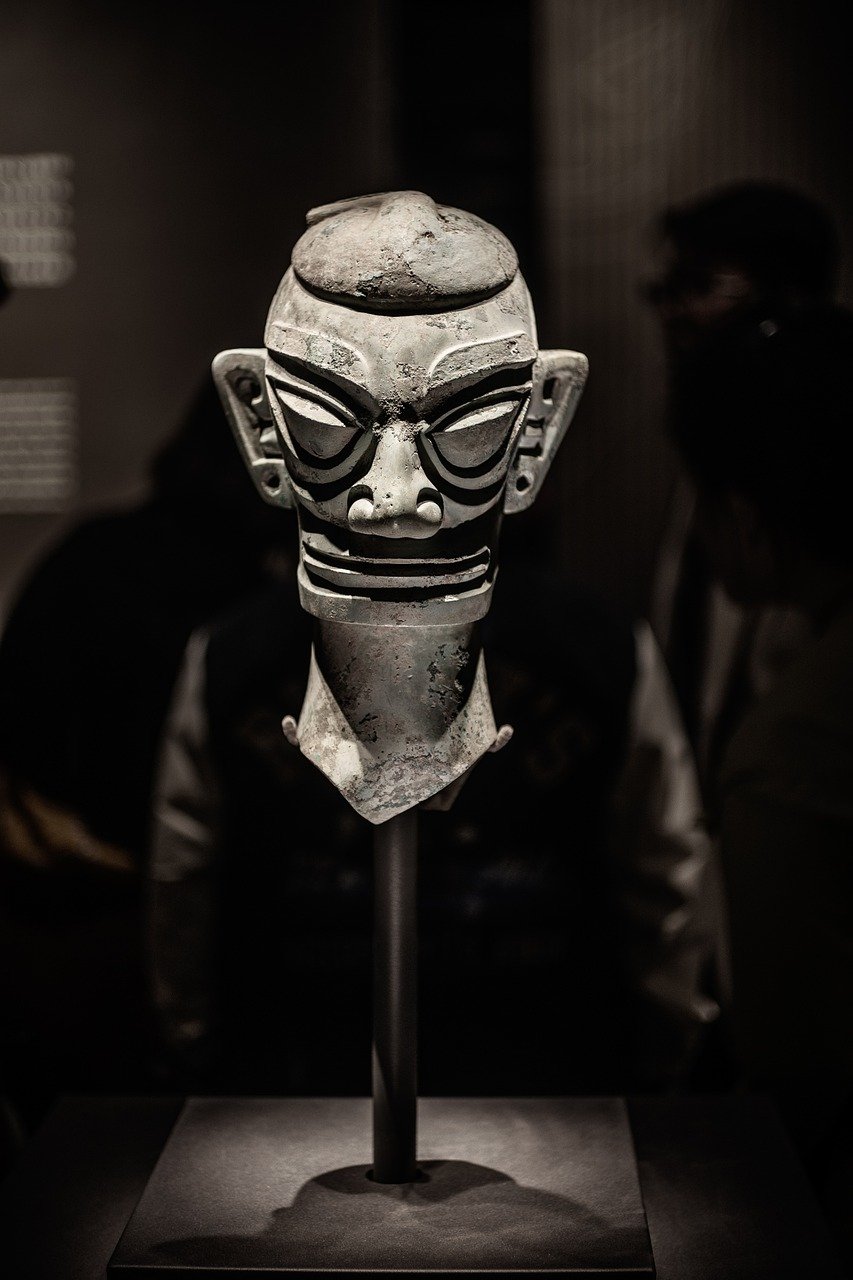

Visually, Shu is depicted as a man with a plumed headdress signifying a single ostrich feather, akin to Maat’s attire. This feather also doubles as a hieroglyph that phonetically relates to Shu’s name, which may translate to “he who rises” or “emptiness,” originating from the verb “to be empty.” At times, Shu is represented as a lion, as evident in a shrine from the 30th Dynasty that likely housed a lion cult statue of Shu, exquisite and crafted from silver and gold.

Shu is linked to the Egyptian conception of eternity manifested in cycles, known as neheh, while Tefnut is associated with djet, which represents the unchanging aspects of eternity. Shu is particularly connected to the enduring cycle of birth, death, and rebirth of rulers, illustrating how air breathes life into the cosmos, as elaborated on later.

Although there seems to be no formal cult dedicated to Shu prior to the New Kingdom, references to him in the Pyramid and Coffin Texts suggest his significance elongated back to the Old Kingdom. These texts often envision the deceased ascending to the heavens via the essence of Shu, symbolizing the cleansing mists, and imply a sacred role in the afterlife and creation.

The New Kingdom marks a period of heightened reverence for Shu, likely due to his emerging solar attributes, which became increasingly vital to Egyptian spirituality leading up to Akhenaten’s radical reforms. Shu’s connection to sunlight allowed his worship to persist even when many other deities were marginalized. In early references from Akhenaten’s reign, Shu appears in the titles of the Aten, illustrating the blending of divine narratives.

As a deity linked to the divine breath, Shu embodies both a cosmic and a personal aspect of existence. His divine influence extends to individual lives, where he plays a crucial role in every breath taken. Throughout later phases of Pharaonic Egypt, Shu’s protective and healing characteristics remained prominent, with people invoking his name for safety and assurance in their daily lives.

One of the key aspects of Shu’s mythology is his role within the Heliopolitan Ennead, which includes a group of nine gods central to the creation myth emphasizing the sun’s significance. This tale often describes the primordial waters from which Atum emerges, leading to the births of Shu and Tefnut. The narrative highlights a non-linear view of creation, asserting the existence of these god attributes before their birth, illustrating the profound relationship between life and creation in Egyptian mythology.

Shu and Tefnut eventually form a partnership, producing Geb (the earth) and Nut (the sky), and this interplay leads to a cosmic separation — Shu intervenes to prevent anger between his children, a depiction which becomes iconic in his representation. Shu’s action symbolizes the organization of the world: earth below, sky above, and the life-sustaining air in between, serving as an allegory for the cycles of day and night.

In addition to these myths, Shu features prominently in stories surrounding the winter solstice where he pursues Tefnut, representing the sun’s trajectory in the heavens. While not classified strictly as a solar deity, his roles blend with aspects associated with solar gods like Re, particularly as a guardian during Re’s nightly journey.

Shu’s lineage extends to the kingship mythology of Ancient Egypt; he embodies a foundational aspect of the social order established by the Heliopolitan creation narrative and continues through a succession of divine kingship. The narrative emphasizes a seamless royal lineage extending from Horus to the contemporary Pharaohs, albeit with a nuanced understanding of the realities of political power transitions.

After Atum’s celestial retirement, Shu assumes kingship, often depicted as an effective ruler. However, conflicts with his son Geb yield a narrative of rebellion and turmoil, reflecting anxieties surrounding the legitimacy and stability of leadership in Egypt. The dynamics among these entities serve as metaphors for the precarious nature of governance.

Ultimately, Shu represents the very essence of air, sunlight, and their interrelationship with existence. His multifaceted nature and associations elude tidy categorizations typical in modern interpretations. The interplay between Shu and Tefnut, the fusion with lunar deities, and the flexible definitions encapsulate the richness of Egyptian religious paradigms, compelling us to embrace complexity rather than conformity.

In conclusion, Shu is not only the atmospheric force but also a central figure in the creation, maintenance, and representation of life as understood by the ancient Egyptians.