Exploring Ancient Egyptian Religion

Overview of Ancient Egyptian Beliefs

Ancient Egyptian religion encapsulates the indigenous beliefs of the civilization spanning from the predynastic era (around the 4th millennium BCE) to the eventual decline of traditional practices in the early centuries CE. To truly appreciate this ancient faith, one must understand its inherent ties to Egyptian society during its historical progression, especially from around 3000 BCE onward. Although there might have been remnants of prehistoric beliefs, they arguably hold lesser importance in deciphering the religion in later periods, as the establishment of the Egyptian state significantly transformed the religious landscape.

Integration into Society

Egyptian religious beliefs and practices were intricately woven into the daily lives of its people. It would be an oversimplification to view religion solely as a coherent system; rather, it evolved amidst various nonreligious activities and societal values. Over the course of 3,000 years, ancient Egyptian religion experienced notable shifts in focus and practice, yet it consistently maintained a distinctive character and style throughout different epochs. It is crucial to broaden the definition of religion beyond simply the veneration of gods and pious behavior.

Ritualistic behaviors included interactions with the deceased, divination, the use of oracles, and magical practices that sought to manipulate divine powers and associations. The two pivotal aspects of public religion were centered around the pharaoh and the deities. The king held a singular position as an intermediary between humanity and the divine, participating actively in the celestial realm, and erecting monumental religious structures for his afterlife journey.

The Pantheon of Deities

The pantheon of ancient Egyptian gods comprises a striking variety of representations, which often included animal forms or hybrid figures with human bodies and animal heads. Prominent deities included the sun god, who had multiple names and facets associated with various supernatural entities in a solar cycle akin to the daily transition from night to day, and Osiris, revered as the god of the dead and the ruler of the afterlife. Alongside his wife, Isis, Osiris gained significant prominence throughout the first millennium BCE, especially during periods when worship of the sun god started to wane.

Cosmology and Order

The ancient Egyptians perceived the cosmos as comprising both the divine and the earthly realms, with Egypt positioned as the center of existence. Surrounding these realms was chaos—disorder from which order emerged and to which it could potentially return. The pharaoh’s fundamental duty was to ensure the continued favor of the gods in maintaining this order against encroaching chaos. This somewhat melancholic cosmological view was closely tied to the sun god and the cyclical nature of the sun. It served as a potent legitimization of the king and the elite’s role in safeguarding societal order.

Despite this somewhat grim view, the public depictions of the cosmos were portrayed positively, often illustrating the king and deities in a state of ongoing interaction and harmony. This portrayal underscored the fragility of the established order. Monuments reflected strict decorum regarding what could be depicted, how it was presented, and in which situations such representations were appropriate. This decorum further reinforced the concept of order.

Divergent Beliefs

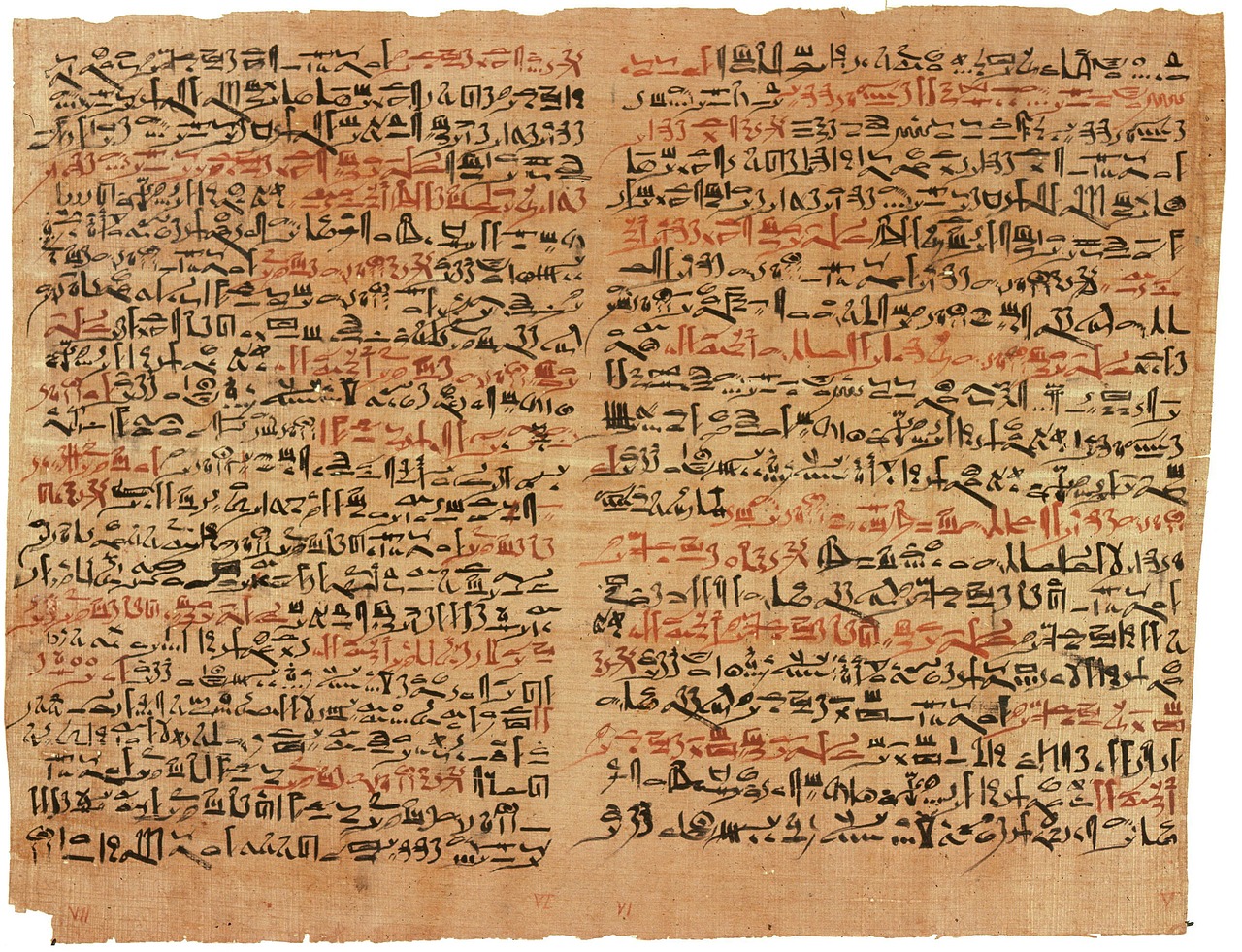

These religious beliefs and practices are predominantly understood through monuments and documents produced for and by the king and the elite classes. In contrast, the spiritual life of the average citizen remains less well-documented. While it is reasonable to assume that fundamental similarities existed between the elite and the populace’s beliefs, significant disparities cannot be entirely excluded.